The Wake-Up Call

When COVID-19 hit, the world realized just how fragile public health systems can be. Hospitals filled up, supply chains broke, and misinformation spread faster than the virus itself.

For public health leaders, it was a turning point. They learned the hard way that pandemics don’t follow schedules — and that preparation has to be constant, not reactive.

Dr. David Banach of Woodbridge, CT, an infectious disease physician and hospital epidemiologist, remembers those early months clearly. “Every morning felt like we were rewriting the playbook,” he says. “We had to make fast decisions with incomplete data regarding infection prevention strategies and guidelines. That pressure changes how you think about readiness.”

Now, years later, leaders like Banach are applying those lessons to prepare for whatever comes next — whether it’s another virus, a drug-resistant bacteria, or an entirely new kind of public health emergency.

What COVID-19 Taught Public Health Experts

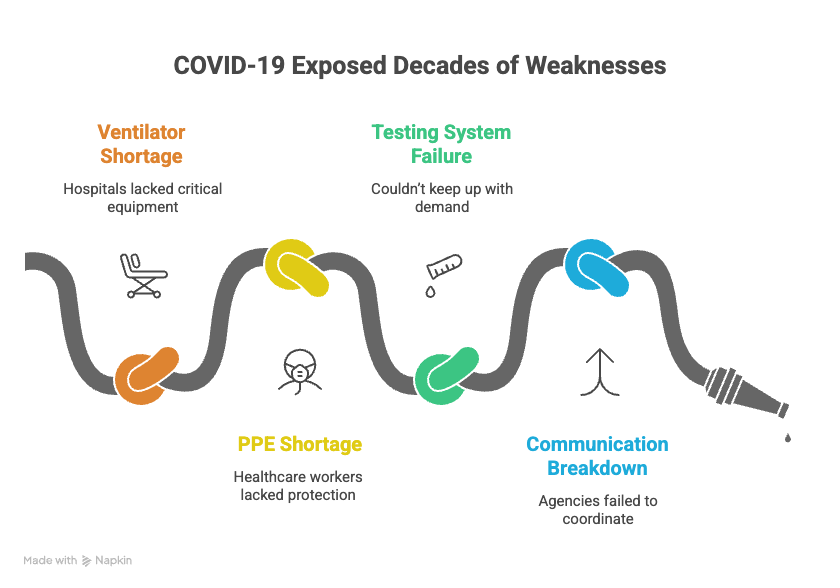

COVID-19 exposed weaknesses that had been building for decades. Hospitals ran short on ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE). Testing systems couldn’t keep up. Communication between local and federal agencies broke down.

But it also showed what works. Vaccines were developed in record time. Contact tracing programs improved. Data sharing became faster.

According to the CDC, the U.S. reported over 100 million confirmed cases and more than 1 million deaths during the pandemic. But experts agree those numbers would have been much worse without coordinated efforts from healthcare professionals and scientists.

Banach notes, “The collaboration we saw between hospitals, universities, and public agencies was unlike anything before. That level of teamwork has to continue — not just during crisis, but in between them.”

Building Systems That Can Bend Without Breaking

Preparedness isn’t about stockpiling supplies anymore. It’s about flexibility. Public health systems must be able to scale up quickly, communicate clearly, and adapt as new information comes in.

One major change has been the creation of real-time disease monitoring systems. Hospitals now track infection trends daily and share that data with state and federal agencies. This helps detect outbreaks before they spread widely.

In Connecticut, several hospitals have partnered with the Connecticut Department of Public Health to build unified reporting tools. These systems make it easier to identify spikes in respiratory illness or antibiotic-resistant infections.

Banach says, “We can now spot trends in days that used to take weeks. That’s how you stop small problems from becoming full-blown crises.”

The Human Factor: Communication and Trust

Public health isn’t just about data — it’s about people. During COVID-19, communication often failed. Conflicting messages about masks, vaccines, and safety guidelines caused confusion.

A 2022 Pew Research Center survey found that 44% of Americans said they were unsure who to trust for health information during the pandemic. That’s a big problem.

Leaders learned that communication has to be simple, consistent, and transparent. Jargon doesn’t work. People want clear answers they can act on.

Banach recalls speaking with community groups during 2020. “We held small Q&A sessions at local churches and schools. People wanted to ask real questions — not just hear statistics. When we listened, trust started to rebuild.”

That personal approach is becoming part of the new public health strategy: meeting people where they are and making science human again.

The Role of Technology and Rapid Response

One of the biggest wins during the pandemic was the ability to share information quickly. Laboratory testing improved dramatically. Sequencing of virus strains went from taking weeks to just days.

This speed helps scientists identify new variants early. The faster that happens, the faster vaccines and treatments can be updated.

Hospitals are also improving response plans for supply shortages. Some facilities now use inventory tracking systems that monitor PPE, ventilators, and critical drugs in real time. If supplies dip too low, alerts go out instantly.

These changes may seem small, but they save time — and time saves lives.

Training the Next Generation

The pandemic created a new wave of public health interest. Enrollment in public health degree programs increased by more than 20% nationwide between 2020 and 2022, according to the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health.

Banach, who teaches at multiple universities in Connecticut, says students now ask sharper questions. “They’re not just learning theory,” he explains. “They want to know what it’s like to make decisions under pressure, with real consequences.”

Simulation training — mock outbreak drills, communication exercises, and hospital coordination tests — has become a major focus. These programs teach young professionals how to lead in crisis, not just study one.

Fighting the Next Big Threat

While pandemics get most of the attention, experts say other threats are already here. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria, for example, kill about 35,000 people in the U.S. each year, according to the CDC.

Climate change is another issue. Rising temperatures expand the range of mosquito-borne diseases like West Nile virus and dengue fever.

Public health leaders are preparing for both. Hospitals now combine infectious disease surveillance with environmental monitoring to track potential outbreaks tied to weather patterns.

Banach warns, “We can’t think in silos anymore. Infectious disease, environment, and community health all overlap. Preparing for one means preparing for all.”

Actionable Steps for Better Preparedness

1. Strengthen Communication Channels:

Create clear, simple messaging that can be easily updated and shared across agencies, media, and the public.

2. Support Ongoing Training:

Regular simulation exercises keep healthcare teams ready for rapid changes. These should happen at least twice a year in hospitals and clinics.

3. Invest in Early Detection:

Expand real-time disease monitoring and lab capacity. Fast results are key to containment.

4. Promote Collaboration:

Partnerships between hospitals, universities, and state agencies build consistency. Sharing data saves time.

5. Build Community Trust:

Engage with local organizations and schools to make health information accessible and understandable.

6. Protect Healthcare Workers:

Ensure access to PPE, mental health resources, and flexible staffing plans during crises.

Lessons for the Future

The next public health crisis won’t look exactly like COVID-19. It might spread faster, hit different regions first, or come from an unexpected source. But the mindset of readiness — constant, flexible, team-based — is what will make the difference.

For leaders like Banach, the goal is simple: stay ready, stay connected, and never underestimate the power of communication. “Preparation doesn’t end when the headlines fade,” he says. “It’s the quiet work between crises that protects people the most.”

A Culture of Continuous Readiness

Public health success doesn’t come from panic. It comes from practice. The systems being built today — smarter surveillance, better training, and clearer communication — are the foundation for tomorrow’s safety.

COVID-19 was a wake-up call. But it also sparked innovation, teamwork, and resilience. Those lessons will shape how Connecticut, and the rest of the world, responds when the next threat arrives.Because preparedness isn’t a plan you dust off once in a while. It’s a habit. And for professionals like David Banach Woodbridge, CT, it’s a lifelong mission to keep communities healthy — no matter what comes next.